Born into royalty

Prince Rogers Nelson was born on June 7, 1958, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, a city with a rich and surprisingly complex history that would shape the young artist in significant ways.

Prince’s parents, John Lewis Nelson and Mattie Della Shaw, found one another through music, and when their child was born they gave him John’s stage name, Prince Rogers.

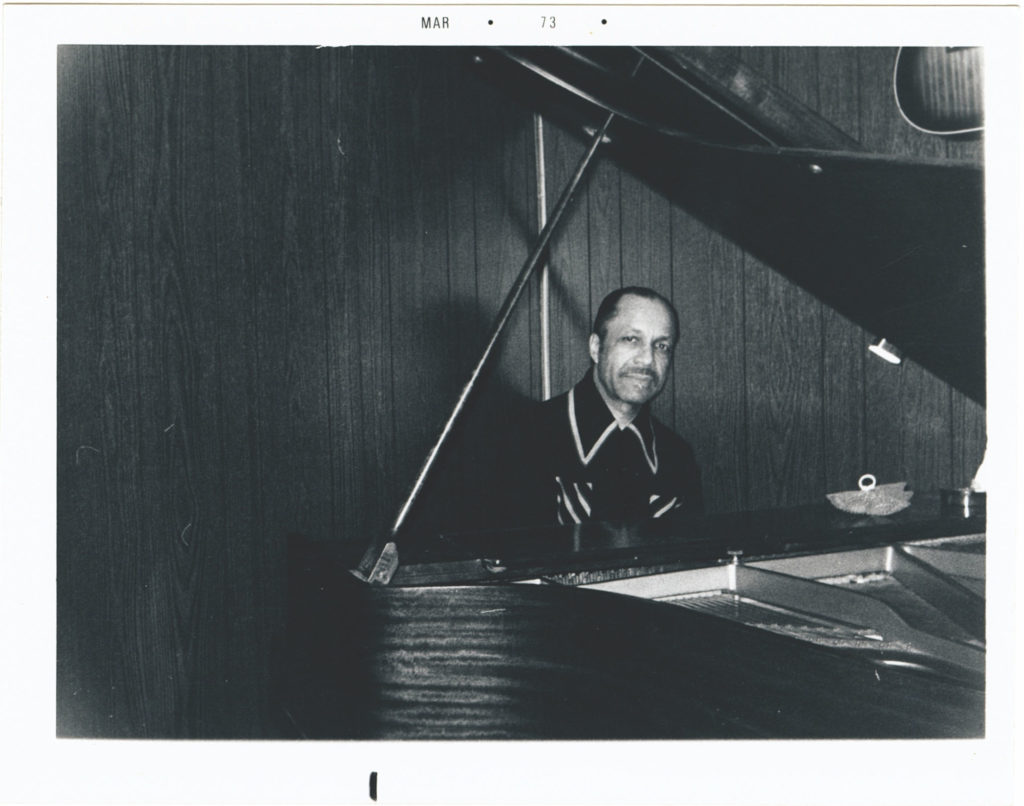

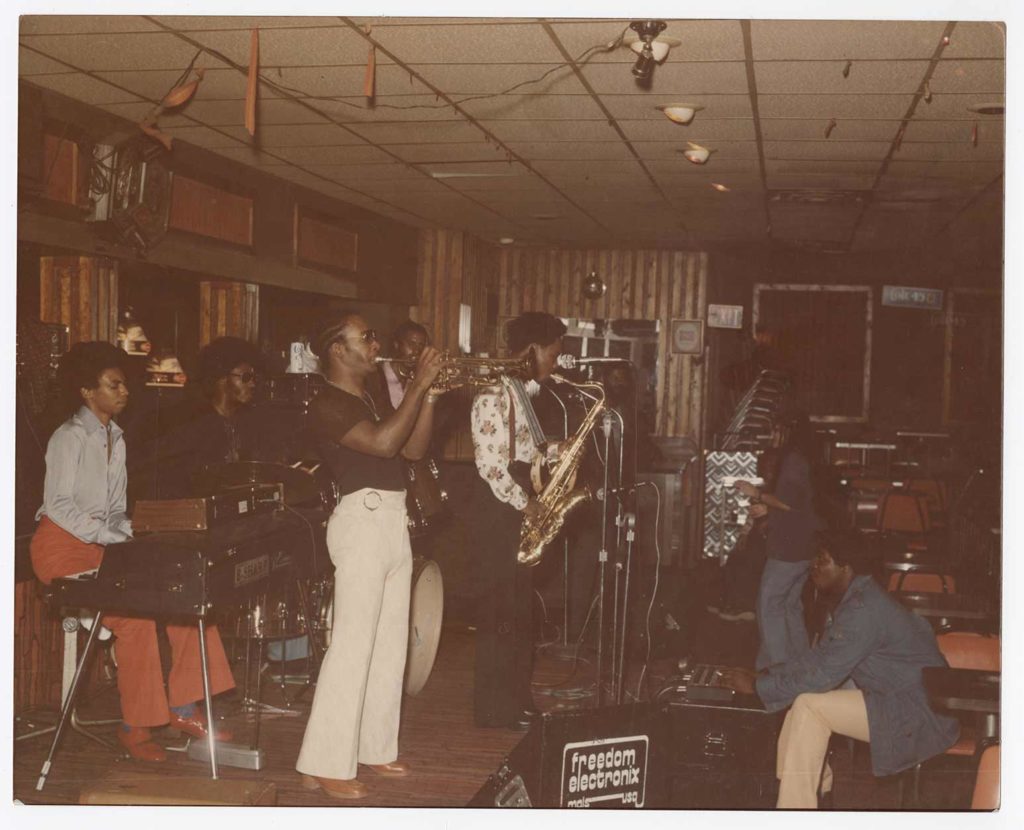

In the 1950s John Nelson had made a name for himself in the music scene playing piano and leading the Prince Rogers Trio, a jazz group who would play in clubs and community centers on the North Side like the Phyllis Wheatley House, a historic building that opened in 1924 to provide social services for African-American families moving to North Minneapolis. It was while he was playing with his group at the Blue Note jazz club that he first met Prince’s mother, Mattie, and recruited her to sing in his band. Their musical union developed into a romantic partnership as well, and almost exactly nine months after marrying (their wedding was August 31, 1957), they welcomed their son Prince into the world.

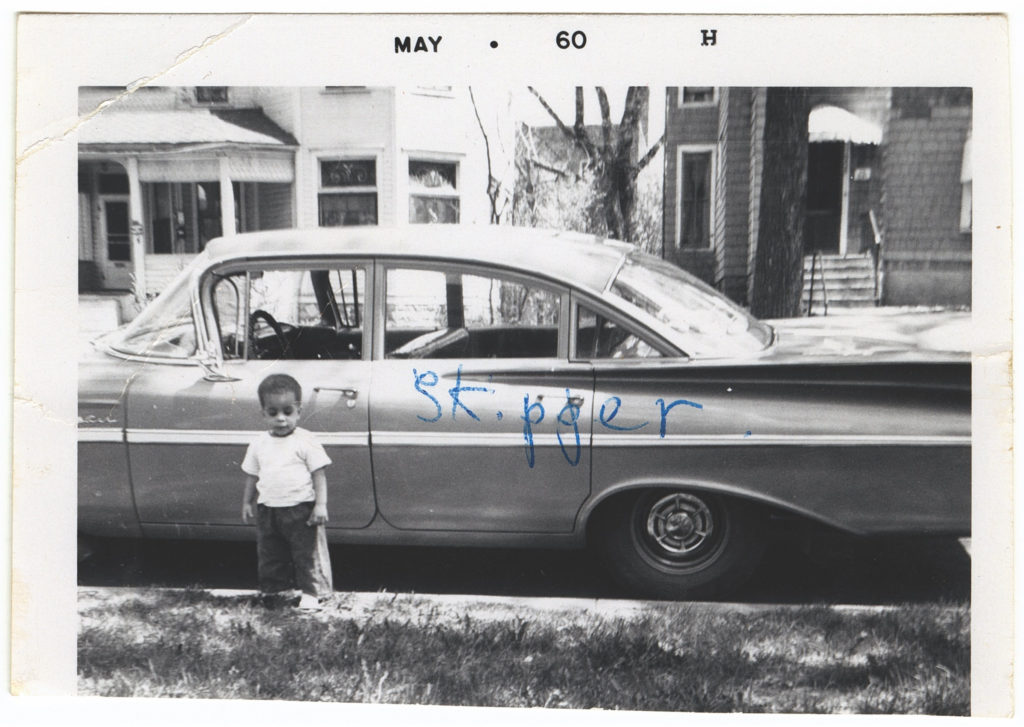

“There were 2 Princes in the house where we lived,” Prince wrote in the first pages for his memoir, The Beautiful Ones. “The older one with all the responsibilities of heading a household & the younger one whose only modus operandi was fun.” In those nascent days, the younger Prince was often referred to by his nickname, Skipper.

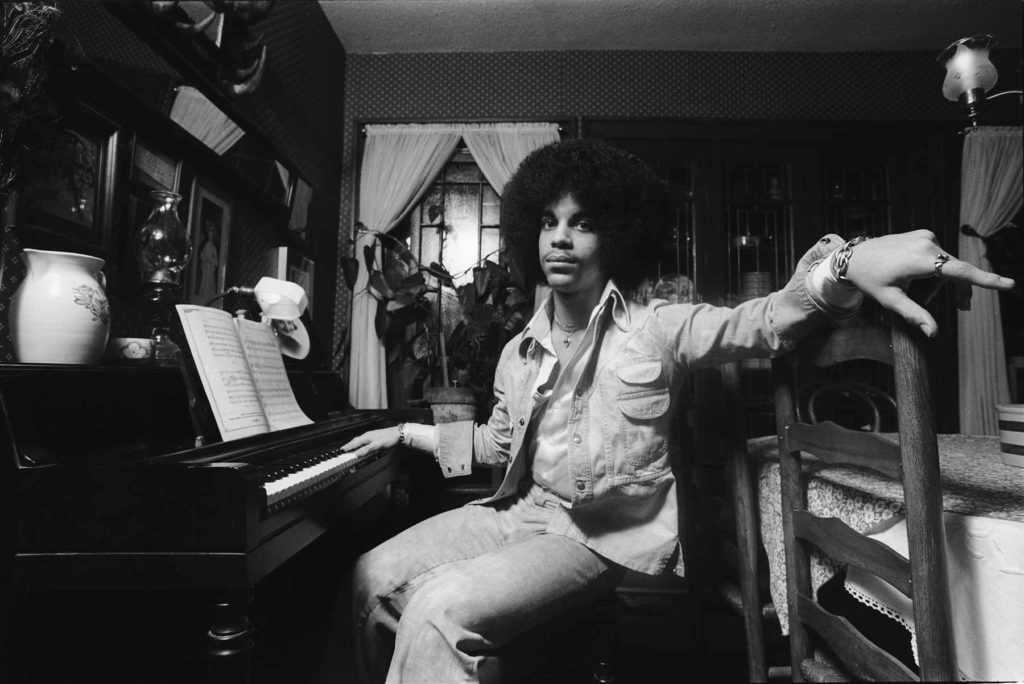

From a very early age, Prince remembered music filling his home. At his reflective, autobiographical Piano and a Microphone concert at Paisley Park on January 21, 2016, Prince opened the show by sharing a memory of being enchanted by the sight of his father’s piano when he was just three years old.

“Here comes dad… I’m not supposed to touch his piano… but I want to play it so bad.”

John and Mattie separated when Prince was 7 and eventually divorced. When Prince began working on his memoir in early 2016, he reflected on that jarring shift in his reality. “Eye had no idea what impact that would have on me. Eye was 7 years old & more than anything Eye just wanted peace. A quiet space where Eye could hear myself think & create,” he wrote. Once John moved out of the home, it gave Prince the courage to start playing the piano himself, picking out the melodies to theme songs from television shows like Batman and The Man from U.N.C.L.E.

“I can’t play piano like dad, though—how does dad do that?”

As time passed and Prince matured, he progressed from being intimidated by his father’s musical talent to being inspired by it. When he was 12, he lived with his father for a brief time and had the chance to watch up close as he juggled a day job at Honeywell with late-night gigs and the nonstop urge to make music.

“He told me one time that he has dreams where he’d see a keyboard in front of his eyes and he’d see his hands on the keyboard and he’d hear a melody. And he can get up and it can be like 4:30 a.m. and he can walk right downstairs to his piano and play the melody,” Prince told Musician Magazine in 1981 (though the interview wasn’t published until 1983). “And to me that’s amazing because there’s no work involved really; he’s just given a gift in each song.”

When the world was introduced to Prince through the film Purple Rain in 1984, it was easy to assume that the movie’s storyline was an exact depiction of Prince’s early musical life. As Prince noted many times, Purple Rain was only partly inspired by actual events, and partly dramatized. One parallel, however, is that they were both driven to constantly create music, and shared an unspoken creative bond. They collaborated on significant songs in Prince’s catalog like Purple Rain’s “Computer Blue” and “Father’s Song,” and Around the World in a Day’s “The Ladder.”

“We have the same hands. We have the same dreams. We write the same lyrics, sometimes. Accidentally, though. I’ll write something and then I’ll look up and he’ll have the same thing already written,” Prince told Ebony in 1986. Thirty years later, sitting at his piano at Paisley Park, he summarized their long and complex relationship in a few short, simple sentences: “I thought I’d never be able to play like my dad, and he never missed an opportunity to remind me of that,” he said. “But we got along good. He was my best friend.”

From child prodigy to bandleader

When Prince entered junior high, he was developing a wide array of interests — in addition to experimenting with various musical instruments, he was also on the baseball, football, and basketball teams at school with his step-brother, Duane. Sports and music provided a sense of stability in what was otherwise an uncertain time in Prince’s life. His mother, Mattie, had remarried, and Prince was having trouble adjusting to his new stepfather, Hayward Baker. Prince ran away from home for the first time when he was in junior high (“I think maybe I was too much of a punk back then to deal with the situation I was in,” he would later tell Ebony), and he spent several years bouncing around between his dad’s place in North Minneapolis, his aunt’s house in South Minneapolis, and a home where he would develop his first meaningful creative partnership and rehearse for hours with his first band.

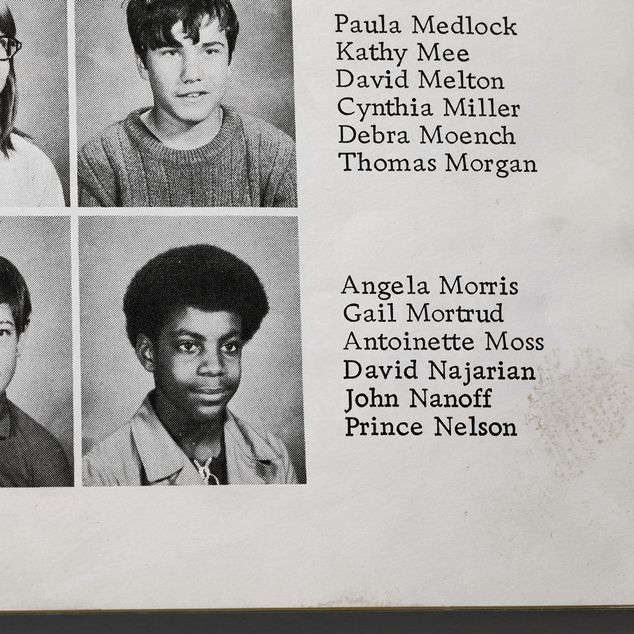

Prince spent the majority of 7th and 8th grade attending Bryant Junior High School in South Minneapolis, but it was during a brief stint attending Lincoln Junior High near his dad’s home in North at the very beginning of 7th grade that Prince met the budding young musician André Anderson, who would later be known as André Cymone. Realizing that they shared a passion for music, Prince and André became fast friends, heading home after school to jam on the many instruments scattered around Prince’s dad’s apartment.

“He sat at his father’s piano and played several television and movie theme songs. I played along on a large-scale ukulele, I think for the first time in his life — and I know for the first time in mine — we found someone in each other who took music and all its possibilities extremely seriously. I think, after that day, we were pretty much inseparable. We hung out all the time.”

It was there that they realized their families already knew each other — their mothers had been friends for years, and André’s father, Fred Anderson, had once been a member of the Prince Rogers Trio. The two families had first crossed paths at church.

“We grew up 1st attending 7th Day Adventist Church where Eye 1st met the Andersons,” Prince wrote in his memoir, The Beautiful Ones. “Fred Anderson and his wife Bernadette were friends of my parents and, though Eye never asked, Eye believe now that Bernadette & my mother secretly had each other’s back when it came 2 their husbands. 4 that matter Eye think that the entire planet has been maintained this long by the feminine principle. Eye can always let my guard down when there’s a woman present.”

Bernadette Anderson had a lasting impact on Prince. When he began working on his memoir in early 2016, Prince intended to set aside an entire chapter just for her. After a short stint living with his aunt, Olivia Lewis, in South Minneapolis, a teenaged Prince moved in with Bernadette and her six children and she became a guiding figure in his life. In fact, “Queen Bernie,” as she was known in the neighborhood, was so instrumental in helping to keep Prince in school and develop his work ethic that she would get a shout-out decades later in one of Prince’s most autobiographical songs, 1992’s “The Sacrifice of Victor”: “Bernadette’s a lady, and she told me / ‘Whatever you do son, a little discipline is what you need / You need to sacrifice.’”

“Prince and my mother, they were quite close — they were really, really close. After all she was responsible for him and his well-being during probably his most formative years. My mother’s main demand and his main responsibility was to help around the house and make it to school on time and maintain good grades. I think that was it, and he did that. That’s what he did.”

Prince’s classmates at Central High School knew that he was a talented musician, and a dedicated one; halfway through sophomore year he had quit the basketball team and was dedicating every free moment to jamming in the music room. But he had an aversion to joining the school band or taking formal lessons — a fact that was noted in his first piece of press ever, a 1976 article in the student newspaper the Central High Pioneer: “He likes Central a great deal, because his music teachers let him work on his own.” Instead, Prince preferred to get most of his music education from their stereo, spending hours with André in the Anderson’s basement listening to rock and folk artists like Joni Mitchell, Maria Muldaur, and Carlos Santana on FM station KQRS, and exploring the rich history of R&B, soul, and funk via the black community radio station KUXL, an AM channel that was only broadcast to a small section of North Minneapolis.

At his January 2016 Piano and a Microphone show, Prince recalled his days listening to KUXL:

"Back then, radio was localized. We had a DJ named Pharaoh Black, and Kyle Ray, and Jack Harris. Jack Harris had his own band, that's how funky he was. He would choose what we listened to, and he had great taste."

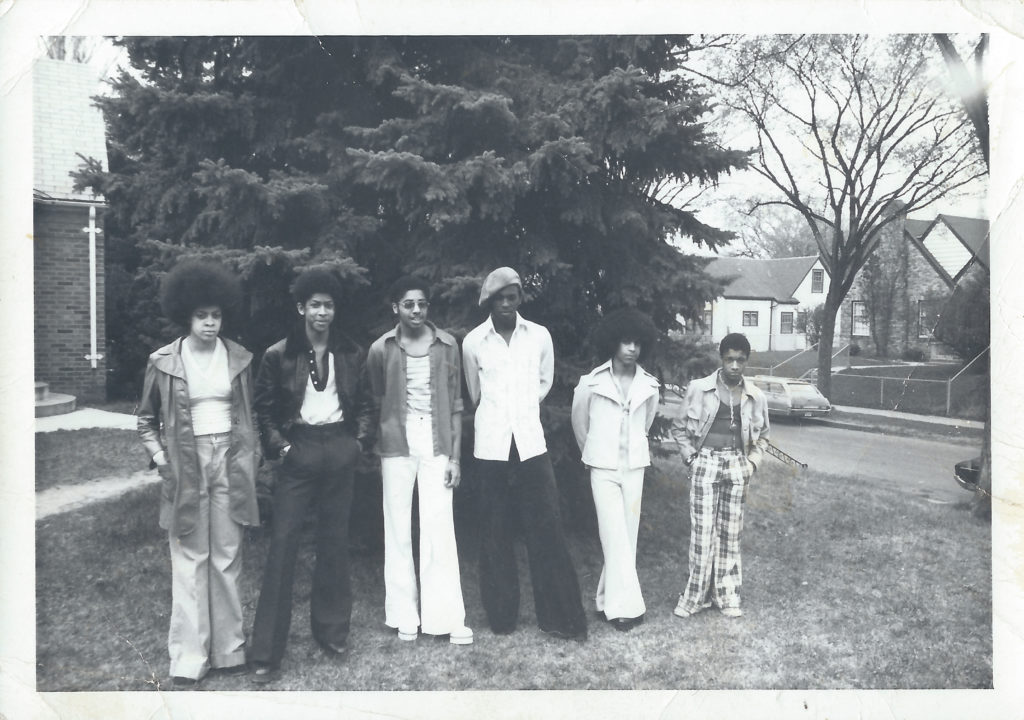

From Grand Funk Railroad to Sly and the Family Stone, Jimi Hendrix to the Jackson 5, Prince listened eagerly and learned it all. Grand Central was starting to get booked not just at community centers in North Minneapolis but at high school proms and homecoming dances across South, and Prince knew that he would have to learn a wide variety of Top 40 hits to appeal to the white teenagers in all parts of the city.

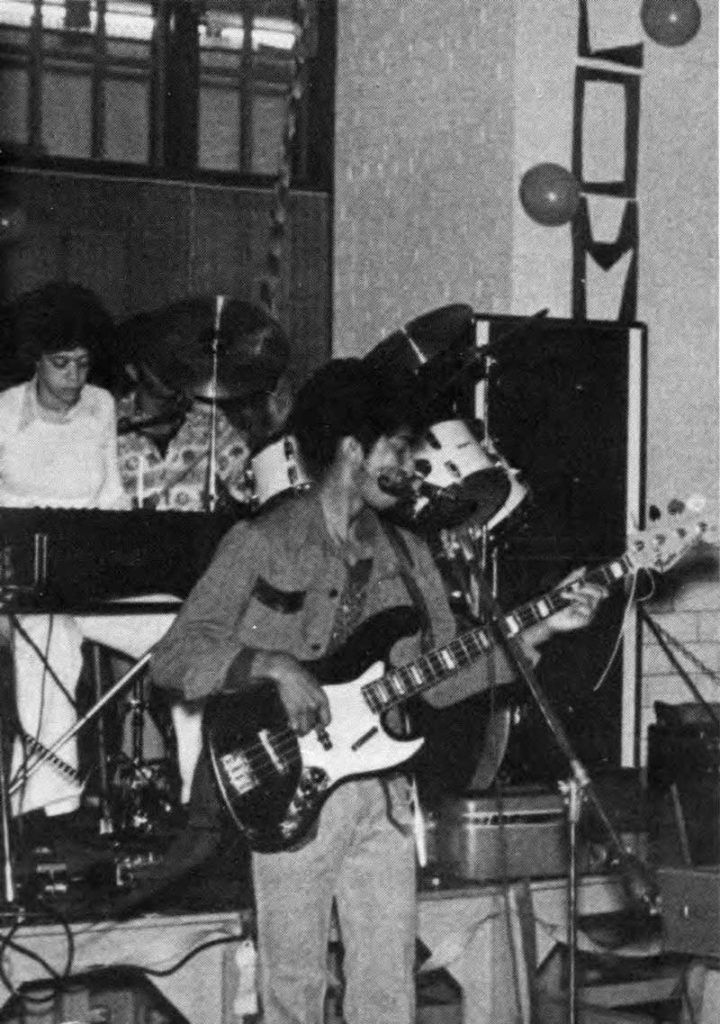

Over the years, Grand Central went through a few lineup changes. The first iteration consisted of Prince, André Anderson, and Prince’s cousin, Charles “Chazz” Smith. Later on, André’s sister, Linda Anderson, joined on organ, Terry Jackson and William Doughty took up auxiliary percussion, and in 1974 Smith was replaced by a young Morris Day on drums. As the band grew, they quickly became one of the youngest, hottest bands on the North Side.

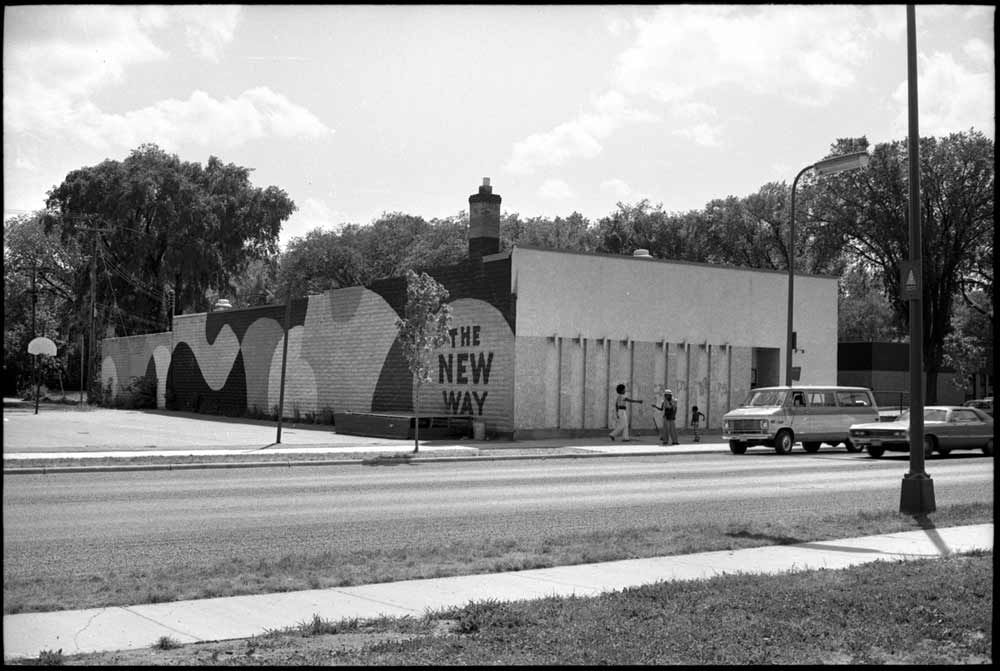

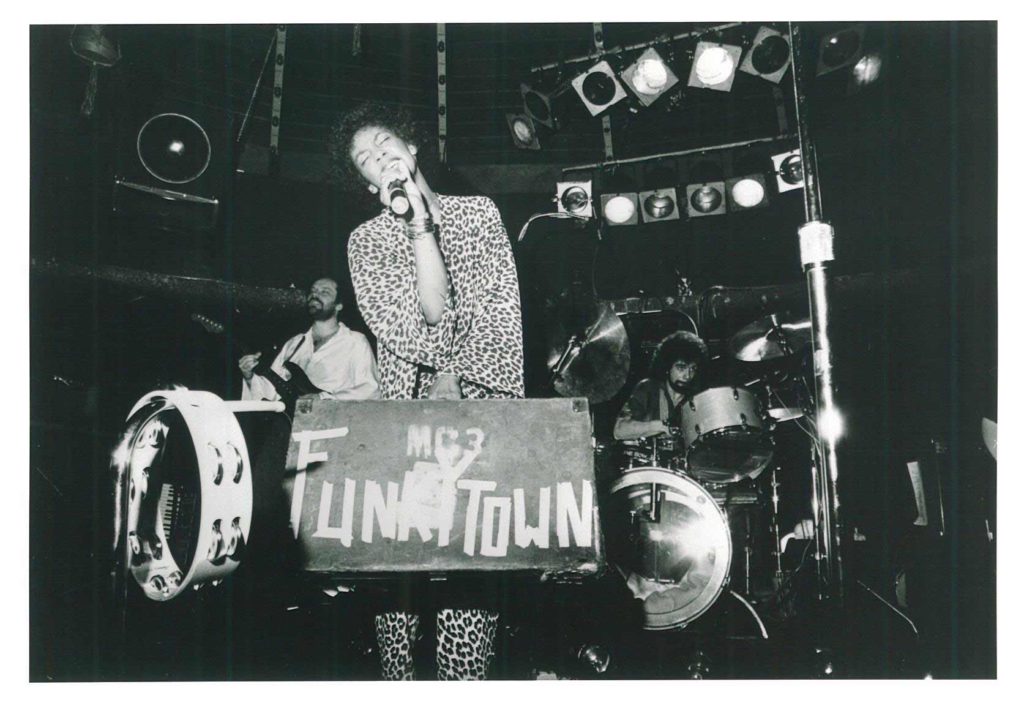

Grand Central would compete for notoriety and bragging rights at neighborhood Battle of the Bands showcases, performing at the Phyllis Wheatley or the Way community centers against bands like The Family, which was led by Sonny Thompson, an early mentor of Prince’s and a future member of the New Power Generation; Flyte Tyme, led by the bassist Terry Lewis, saxophonist David Eiland, and vocalist Cynthia Johnson, who would sing the Lipps Inc. hit “Funkytown”; Mind and Matter, which was led by Jimmy Jam; and Cohesion.

“We jammed a lot with other bands,” Prince told the Aquarian Night Owl in 1981. “There was a lot of competition around ’75. It was a time when there was a lot of spirit. I think that helped me come out of myself. We got in a lot of trouble from other band members if we copied anything [from them], and we gave them a lot of trouble if they copied anything [from us], so it was a real competitive thing. You had to be as out as you could and as different, and as much you as possible.”

It was in these early days that Prince first started to define the sound that he would soon make world-famous: a combination of black and white musical influences that explored the intersection between funk and rock, punk and disco, modern dance music and old-school jazz and blues. Though he didn’t know it yet, by the time he graduated from high school Prince was well on his way to developing the Minneapolis Sound and breaking out of Minnesota.

Prince’s career takes flight

Prince knew he had what it took to land a record deal and record a hit, and as soon as he finished school he hit the ground running. He saved up the cash he earned from a couple of recording sessions with local bands — Sonny Thompson’s band the Family, and the group 94 East, which was led by another of Prince’s early mentors, Pepé Willie — and booked a flight to New York City to stay with his older half-sister, Sharon Nelson, and pitch himself to record labels.

Back home, Prince had recorded a raw demo tape with a respected young Minneapolis producer named Chris Moon, and together they had been polishing a promising new song called “Soft and Wet” that Prince was sure would make a strong impression. While Prince struggled to make the necessary connections that could land him a meeting with a label in New York, Chris Moon decided to take a copy of the “Soft and Wet” demo to an advertising office in the Loring Park neighborhood of Minneapolis that was run by a musician and concert promoter named Owen Husney.

A veteran of the music industry, Husney had been presented with many demo tapes through the years — but something about the song that Moon brought him that day immediately grabbed him. The music was reminiscent of funk and rock greats like Sly Stone, Jimi Hendrix, and Santana, and the vocals were delivered in a powerful yet vulnerable falsetto that captured his imagination.

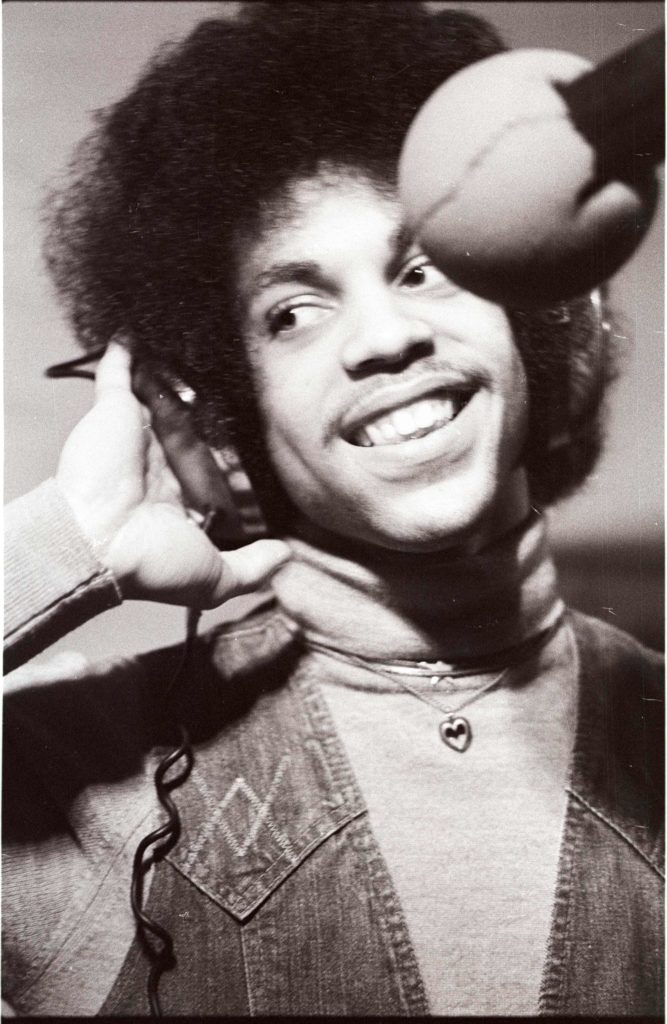

“I was immediately struck that this was something different. I turned to Chris and I said, ‘So, who’s the band here?’ And he said, ‘Well, Owen, it’s not really a band.’ And I thought, ‘Oh no, is it a bunch of studio musicians? Because I don’t really want to work with studio musicians; they can’t tour.’ And he said, ‘No, it’s not a studio band. It’s one kid. He’s just turned 18, and he’s singing everything and playing all the instruments.”

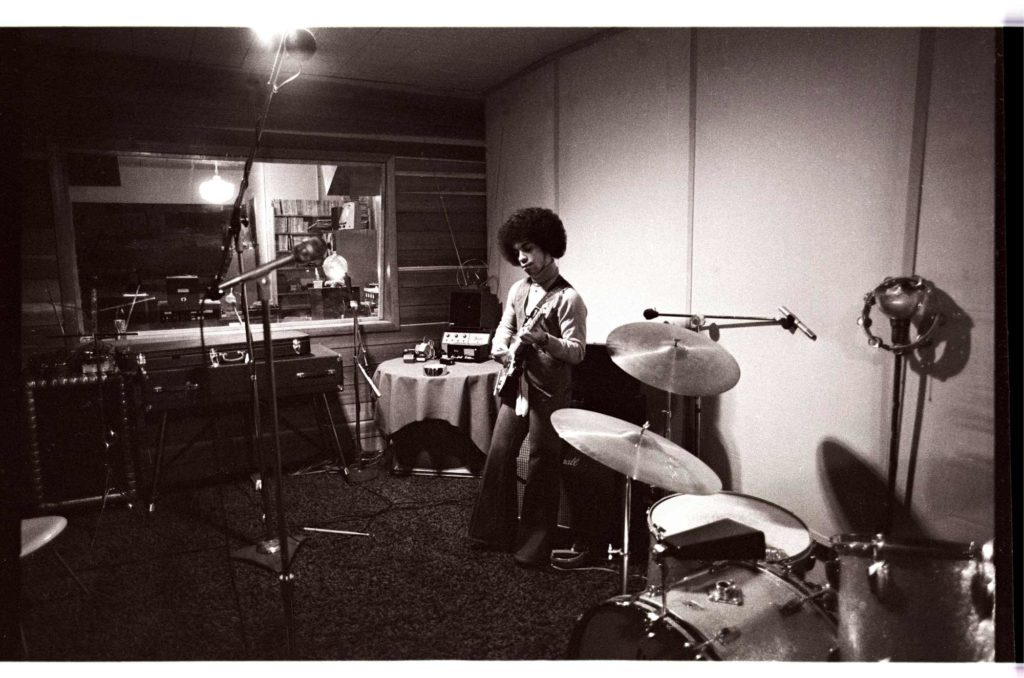

Within a week, Prince was on a plane back to Minneapolis to sign a management contract with Husney, who vowed that he would work around the clock to get Prince the label attention his music clearly deserved. The management deal allowed Prince to move out of the Andersons’ basement and into his first apartment in Uptown, Minneapolis, and connected him with two brothers who would be instrumental in the development of his solo career: David “Z.” Rivkin, an accomplished engineer who helped Prince to refine his demos at the state-of-the-art Sound 80 Studios in South Minneapolis, and his younger brother Bobby “Z.” Rivkin, who was working at both the Moon Sound studios and as a runner at Husney’s ad agency, and who was tasked with driving Prince to his photo shoots and appointments and would soon be tapped to play the drums in Prince’s new band.

“I first met Prince at Moon Sound. I was walking out one day from Studio B, where I was working, walking by Studio A with the door wide open. I heard the most glorious sound I’ve ever heard. I now know that it was the multi-stacked vocals of ‘Baby.’ I looked in, saw the Afro, and got the side-eye look — we all know now what that was — and won him over with a few jokes. And within a matter of minutes, we hit it off.”

Bobby remembers being blown away by Prince’s proficiency in the studio, and watching him go from instrument to instrument to lay down every aspect of the track.

“In the first hour I met him I was dazzled, amazed, and captivated — which remained for my entire life.”

In the evenings, Prince would jam in Owen Husney’s office with André and Bobby, pushing the furniture out of the way and setting up their drums and amps in the middle of the room. When the sun was coming up, they would push the furniture back into place so Owen and his team could pound the pavement and work to get Prince his first record deal.

After some creative wheeling and dealing, Husney managed to set up meetings in Los Angeles with Warner Bros. Records, A&M, and Columbia. Within a week, all three labels were offering to sign Prince. And within a month, Husney had negotiated a three-album deal with Warner Bros., the largest record deal for an untested artist in modern rock history. Much to Prince’s relief, his new manager handled much of the glad-handing, pitching, and business details while Prince focused on writing more songs. When it came time for Prince to attend a lunch with the staff of Warner Bros. to celebrate his signing, Husney started brainstorming creative ways that he and Prince might thank the label for their commitment.

“These type of events were not something that Prince relished going to — as a matter of fact, Prince was probably more comfortable in front of 12,000 people than he would have been in front of maybe 20 people for this signing lunch.”

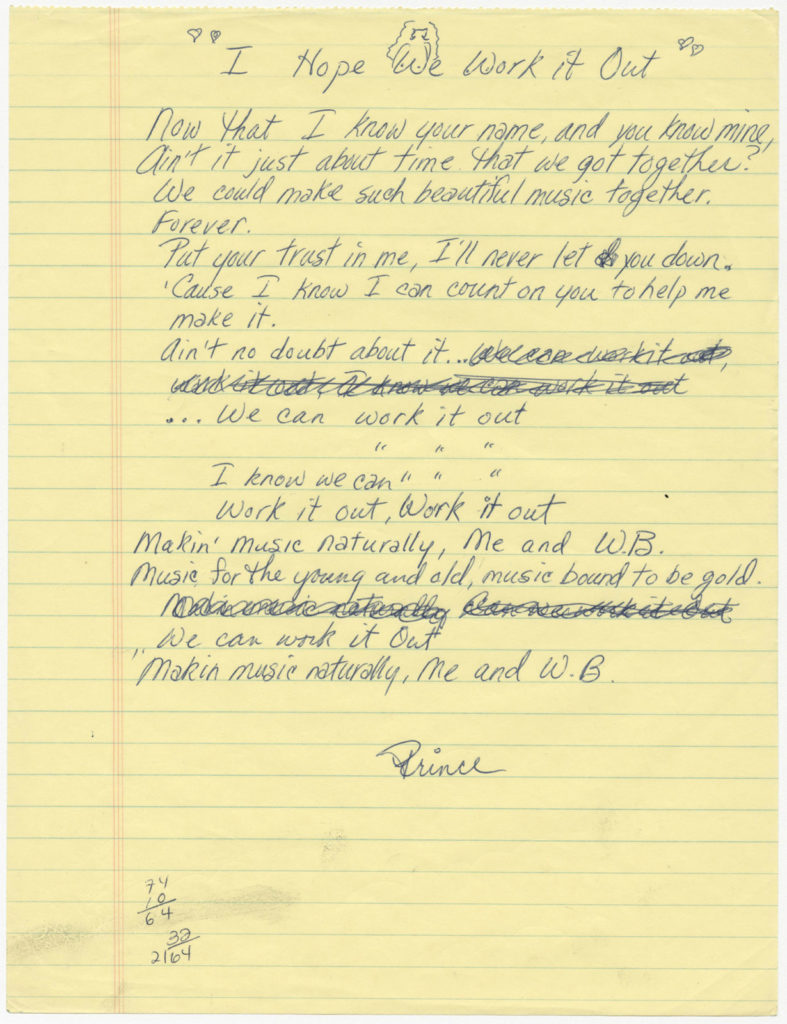

So Prince turned to the language he spoke more fluently than most — music — and wrote and recorded a new song just for the occasion. After the luncheon, Prince brought the executives at Warner Bros. into an office and pressed play on the ominously titled track “I Hope We Work it Out.”

“Everyone was sufficiently blown away with the fact that someone who was 18 years of age had just written a song specifically for a record label. This was Prince showing great faith and asking for trust, and he would in turn give that trust, to make sure that he had a great career. It was a very special time to be there at Warner Bros. watching all of these top executives listen to Prince play this song over the speakers.”

After further negotiations, Prince convinced Warner Bros. to let him not only record all of the instruments but to produce his debut album, For You, by himself, another historic decision. With André at his side, Prince went to the Record Plant in Sausalito, California, to toil away on the album, which took nearly two months of around-the-clock sessions to complete. And when it came time to market the album in 1978, Prince was very specific about the way he wanted to be presented to the world: not as an R&B artist, and not as a black artist, but as a genre-blurring new pop star who could appeal to mainstream audiences and be played on radio stations in every part of every city.

When it came time for Prince to finalize the lineup for his band and translate his solo material to the stage, he knew that the makeup of his band could help him to achieve his mission, too. Bucking the trend of other bands to come out of Minneapolis, Prince assembled what he described as a “rainbow” band: one that was both male and female, black and white; a representation of the same culturally fluid world Prince hoped to create with his sound. When he made his solo debut at the Capri Theater in North Minneapolis, not far from where he first dared to play his dad’s piano all those years ago, Prince was joined by André Cymone and Bobby Z., the keyboardists Gayle Chapman and Matt Fink (a.k.a. “Dr. Fink”), and the guitarist Dez Dickerson.

The band’s live show was still a few years away from the flawless execution and showmanship that Prince would be known for; in one particularly comical moment of technical difficulty, the new FM wireless guitar setup that Dez Dickerson had acquired began malfunctioning, and in the middle of the show it started picking up nearby CB radios and broadcasting them over the PA.

“The shows were monumental for several reasons, as of course the first shows Prince played live as a solo artist; this band’s debut; and the debut of a lot of wireless technology that caused a tremendous amount of radio frequency to come through the guitars — which in hindsight is kind of humorous, but at the time when you’re hearing police calls and fire calls and radio frequency coming through the speakers while you’re trying to play and perform, it was not so funny at the time.”

“A little rough around the edges, but certainly the beginning of something that we could learn from, and Prince became better and better and better, until he polished the edges off into a shining diamond.”

With his work cut out for him, Prince left those Capri Theater shows with a distinct vision of his future. On that night and moving forward, he knew what he wanted to become: an artist who could unite people of all backgrounds through his music, and who could transcend the barriers of the music industry to become one of the most iconic musicians of all time. Prince would tell MTV in 1985:

“I was brought up in a black-and-white world. Yes: black and white, night and day, rich and poor. Black and white. And I listened to all kinds of music when I was young. And when I was younger, I always said that one day I was going to play all kinds of music, and not be judged for the color of my skin but the quality of my work. And hopefully that will continue.”